I’ve having the immense pleasure of wading through the actual copies of dozens of newspapers from the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s for a book that I’m currently writing. Every now and then I stumble across something really special.

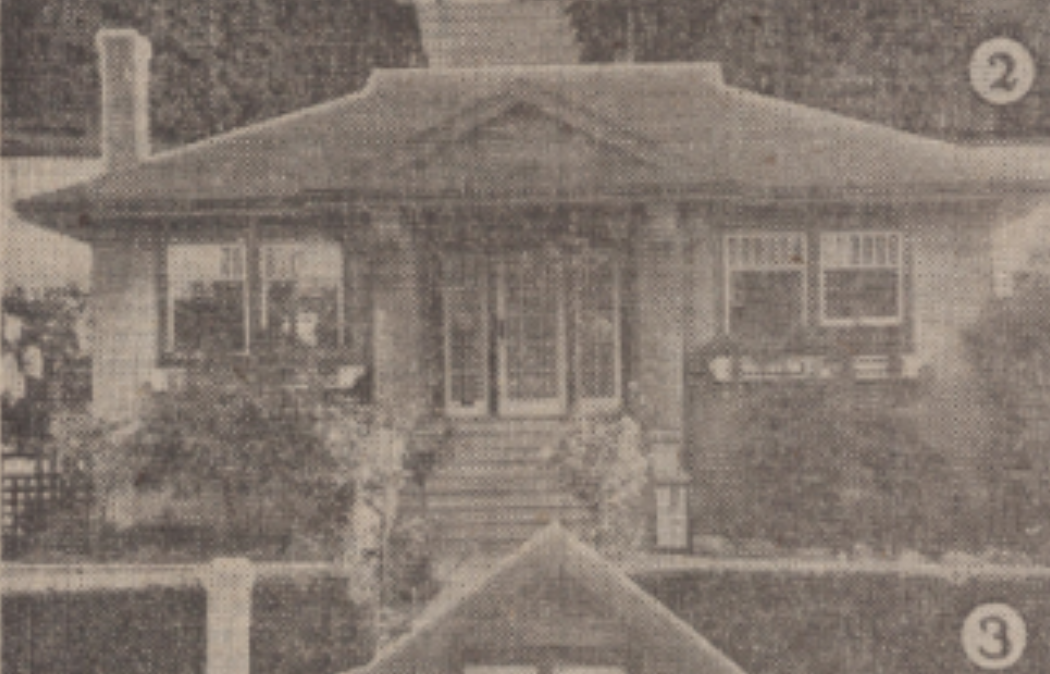

In 1934, the Vancouver Sun bragged that it was “the only evening newspaper owned, controlled and operated by Vancouver Men,” and on page 2 of the Sunday October 6th edition was this short sidebar that ran with the headline “Lovely Vancouver Homes.” Below, in what was clearly an early advertorial disguised as editorial, were the photos of five newish homes that had recently sold. I’m guessing sales would have been somewhat sluggish in the Depression, but the first sentence optimistically stated “Activity continues in Vancouver real estate.”

Naturally, I was intrigued to see if any of the houses still existed.

- 4735 West Sixth: situated in the University district. This beautiful colonial two-storey residence of brick construction on a half-acre lot was purchased by Mrs. K. Rendell through the offices of H.A. Roberts Ltd.

Success. Still there hiding behind a huge hedge and big lot

- 6212 Sperling Street, Burnaby. “The lovely Magee residence” was purchased by Mrs. Olive Dawson of Prince Rupert through the offices of W.H. Moore.

Replaced by two houses that look like every other one in the area.

Replaced by two houses that look like every other one in the area.

- 2350 West 35th Avenue. Attractive Kerrisdale home, beautifully located on the southern slope. Purchased by D.B. Niblock through the offices of Horne Taylor & Co.

Hard to tell with Google maps and a big hedge, but my guess is it’s gone

- 4559 West 2nd Avenue, Point Grey, came with a wonderful view of city, sea and mountains. Ivan Denton is the new owner bought through A.E. Austin and Co.

Miraculously still hanging in there, but looking at its neighbours, perhaps not for long

Miraculously still hanging in there, but looking at its neighbours, perhaps not for long

- 3837 West 16th Avenue – a five bedroom Dunbar house built in 1930, sold to Rev. Osbert Morely Sanford of New Westminster through the offices of Homer J. Moore.

And, yes it’s still there looking much the same as it did 82 years ago, but with some new clothes.

And, yes it’s still there looking much the same as it did 82 years ago, but with some new clothes.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

On September 15, 1954, Danny Brent’s body was found on the tenth green at UBC’s golf course. Stuffed inside his shirt was an early edition of the newspaper, soaked with his blood. There was a half-smoked cigarette inside his shirt where it had dropped from his mouth when he was shot—once in the back and twice in the head with .45-calibre bullets.

On September 15, 1954, Danny Brent’s body was found on the tenth green at UBC’s golf course. Stuffed inside his shirt was an early edition of the newspaper, soaked with his blood. There was a half-smoked cigarette inside his shirt where it had dropped from his mouth when he was shot—once in the back and twice in the head with .45-calibre bullets.

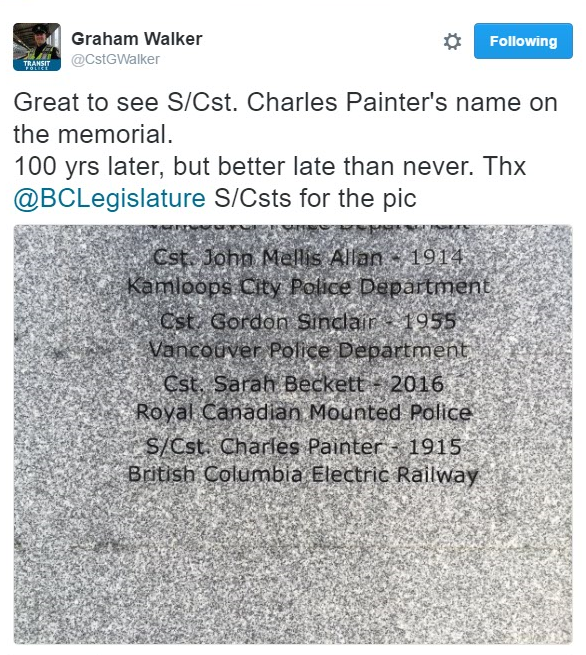

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.

Painter’s murder is still officially unsolved, and his death went unrecognized until Graham and his research. Now his name has been added to the Honour Roll of the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial in Victoria, and Graham is presently trying to secure the funds to have a headstone placed on his unmarked grave at Mountain View Cemetery.